De retour de Somalie, Unni Karunakara, le patron de Médecins sans frontières, a fait des déclarations dans la presse qui méritent d'être soulignées car enfin une association caritative parle vrai en ce qui concerne les promesses faites aux donateurs.

Curieusement dans la dépêche de l'AFP, il n'est pas du tout question de ce point précis :

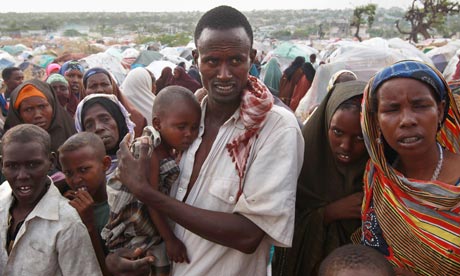

Somalie: le terrain le plus difficile pour les humanitairesNAIROBI — La Somalie, avec sa guerre civile et la multiplication des centres de pouvoir, est le pays le plus difficile au monde pour les humanitaires, contraints de travailler à l'aveuglette face aux conséquences d'une sécheresse historique, estime le président international de Médecins sans frontières, Unni Karunakara.

MSF est une des rares organisations à ne pas avoir quitté la Somalie depuis le début de la guerre civile en 1991, et à travailler aujourd'hui dans certaines régions du sud et du centre contrôlées par les islamistes shebab.

"Mais même avec les réseaux dont nous disposons, nous avons de graves difficultés pour accéder aux régions à problème, et pour mener les estimations indépendantes absolument essentielles pour distribuer de l'aide", souligne le Dr Karunakara. "Aujourd'hui, nous travaillons à la marge" du problème, estime-t-il.

La Somalie "est pour moi le pays le plus difficile" où opérer. "Nous travaillons en Afghanistan, en Irak, mais nous n'avons pas besoin de gardes armés dans ces pays", relève le président international de MSF, de retour d'une visite en Somalie, à Mogadiscio et à Galkayo.

"En Côte d'Ivoire, où il y avait une guerre, il nous a fallu 36 heures pour mener notre première opération. Ici (en Somalie), même obtenir une voiture fait l'objet de négociations".

La sécheresse en Somalie, consécutive à plusieurs saisons sèches, touche 3,7 millions de personnes soit la moitié de la population selon les Nations Unies.

La famine qui en découle sévit essentiellement dans des régions contrôlées par les shebab, où MSF maintient plusieurs programmes d'aide médicale, notamment à Dinsor et à Mareere. "Mais même là, notre accès est très limité", reconnaît le Dr Karunakara.

Les régions officiellement contrôlées par le gouvernement sont, souvent, également difficilement accessibles, ajoute-t-il.

"On parle beaucoup de lever de l'argent et d'amener de l'aide à Mogadiscio. Mais le vrai défi est de savoir comment amener la nourriture du port vers les gens qui en ont besoin", estime le Dr Karunakara.

Du centre et du sud du pays, la crise humanitaire s'est transportée à Mogadiscio, avec l'arrivée de 100.000 personnes fuyant la sécheresse.

"risque d'épidémie élevé"

"Le risque d'épidémie est élevé en raison du surpeuplement et de l'accès très réduit" à des sanitaires et à des points d'eau. MSF a entamé dans la capitale somalienne une campagne de vaccination contre la rougeole, avec 3.000 enfants vaccinés à ce jour, et doit ouvrir la semaine prochaine un centre de prévention du choléra.

"Nous voyons déjà beaucoup de cas d'infections de la peau, des yeux, des poumons, des diarrhées aiguës. Tout ceci est le signe d'une très mauvaise situation hygiénique", s'inquiète le médecin.

Le retrait des shebab de Mogadiscio le 6 août n'a pas radicalement amélioré la situation. "Il y a un vide du pouvoir" dans les quartiers qu'ils ont abandonnés, obligeant les organisations humanitaires à négocier avec quiconque y dispose d'un réel pouvoir, dit le patron de MSF.

"En ce moment nous interviewons 200 personnes pour des postes d'infirmières. Mais chaque embauche doit être discutée avec les chefs de clans, qui vont dire ensuite qui peut être embauché ou pas", relève le Dr Karunakara.

Le patron de MSF rêverait de davantage de visibilité quant à l'ampleur de la crise. Les contrôles effectués par ses équipes suggèrent un taux de malnutrition sévère de près de 30% chez les enfants de moins de cinq ans, mais il souligne qu'"il ne s'agit pas de données scientifiques".

"Nous évitons de donner des chiffres globaux, car de tels chiffres ne signifient rien", estime-t-il, appelant de ses voeux "un accès beaucoup plus ouvert aux régions touchées par la sécheresse, afin que nous puissions y mener de vraies estimations".

En revanche, dans ce papier de Tracy McVeigh dans les colonnes du Guardian, le journaliste se fait bel et bien l'écho des propos de Unni Karunakara que tous les fundraisers devraient conserver à l'esprit : ne pas faire des promesses qui sont sans rapport avec la réalité.

Charity president says aid groups are misleading the public on Somalia

Médecins Sans Frontières executive says charities must admit that much of the country can't be helped

The head of an international medical charity has called on aid agencies to stop presenting a misleading picture of the famine in Somalia and admit that helping the worst-affected people is almost impossible.

The international president of Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), Dr Unni Karunakara, returned from Somalia last week and said that, even though there was chronic malnutrition and drought across east Africa, hardly any agencies were able to work inside war-torn Somalia, where the picture was "profoundly distressing". He condemned other organisations and the media for "glossing over" the reality in order to convince people that simply giving money for food was the answer.

According to Karunakara, agencies have been able to provide medical and nutritional care for tens of thousands in camps in Kenya and Ethiopia, which have been receiving huge numbers of refugees from Somalia. But trying to access those in the "epicentre" of the disaster has been slow and difficult. "We may have to live with the reality that we may never be able to reach the communities most in need of help," he said.

Karunakara said that the use of phrases such as "famine in the Horn of Africa" or "worst drought in 60 years" obscured the "man-made" factors that had created the crisis and wrongly implied that the solution was simply to find the money to ship enough food to the region.

He described Mogadishu, the Somali capital, as dotted with plastic sheets supported by twigs, sheltering groups of weak and starving people who had walked in from the worst-affected areas in southern and central Somalia. "I met a woman who had left her home with her husband and seven children to walk to Mogadishu and had arrived after five days with only four children," he said.

"MSF is constantly being forced to make tough choices in deploying or expanding our activities, in sticking to our principles of neutrality with the daily realities of people going without healthcare, without food. Our staff face being shot. But glossing over the man-made causes of hunger and starvation in the region and the great difficulties in addressing them will not help resolve the crisis. Aid agencies are being impeded in the area.

"MSF has been working in Somalia for 20 years, and we know that if we are struggling then others will not be able to work at all. The reality on the ground is that there are serious difficulties that affect our abilities to respond to need."

He said charities needed to start treating the public "like adults". He went on: "There is a con, there is an unrealistic expectation being peddled that you give your £50 and suddenly those people are going to have food to eat. Well, no. We need that £50, yes; we will spend it with integrity. But people need to understand the reality of the challenges in delivering that aid. We don't have the right to hide it from people; we have a responsibility to engage the public with the truth."

Chronic malnutrition, said Karunakara, is not new in east Africa and needs long-term action. "The Somali people have been living in a country at war, with no government, for 20 years, with several long periods of hardship, of famine and drought. This harvest failure is just what has tipped them over the edge this time, a catastrophe made worse," he said.

A brutal war between the transitional government, which is backed by western nations and supported by African Union troops, and armed Islamist opposition groups, notably al-Shabaab, is ongoing in Somalia. Fierce clan loyalties keep independent international assistance away from many communities, meaning that Somalis are trapped between various forces, depriving them of food and healthcare for political reasons.

"We face constant difficult challenges over simple things like a new nurse or getting a car," said Karunakara. "When we need to be saving lives with a fully fledged medical response, we constantly need to be communicating with both sides in a war, reminding them what humanitarian aid is. One needs only to look at how few charities are working in Somalia."

Ian Bray, a spokesman for Oxfam, said it was unhelpful for aid agencies to be seen to be arguing with each other.

"We're being honest with donors and we have always been honest," said Bray. "A drought is a natural occurrence; a famine is man-made. We don't go around to people saying we have a magic wand, give us £5 and we will make Africa feed itself. We do say give us £5 and we won't use it to give you a history of Somalia, but we will use our expertise to save lives. This is what the bargain is we make with our donors. If you support us, we will do our level best to alleviate the distress for those people in most dire need."

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire